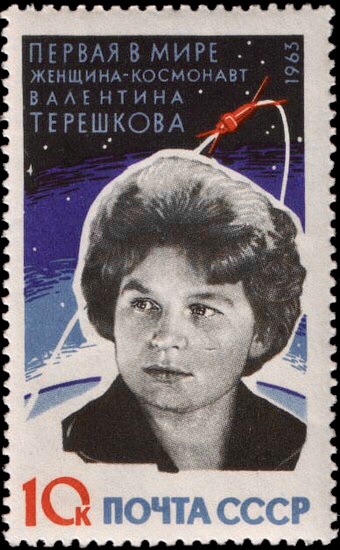

Less than a hundred years ago, no woman had ever flown solo across the Atlantic from Europe to North America. Yet as of March 2023, seventy two women have flown in space. The first woman was Valentina Tereshkova who flew aboard the Russian Vostok 6 in 1963, only twenty seven years after Beryl Markham successfully flew from Abingdon, England to Nova Scotia, Canada.

The early transatlantic flights accomplished similar goals to the early transatlantic steamer voyages. Firstly they were testing the capabilities of the crafts, contributing to the knowledge of the best routes to take, seeking contracts for postal deliveries, and wanting to expand into passenger traffic.

Crossing the Atlantic held many dangers, again the similarities are profound. The design of the craft needed to be robust enough to withstand the weather vagaries which were not just seasonally variable. Extreme winds and squalling rains could just limit vision, and create currents of turbulence especially at the lower altitudes that earlier aircraft demanded. When combined with high seas and strong currents shipping became vulnerable and design failures could become deadly.

The prevailing winds on the crossings are generally from west to east. This impacts on travel times and fuel usage. Travelling east to west took longer and used more fuel because it was going against the wind. Either on sea or in the air, the need to increase the fuel load reduced the amount of space for both cargo and passengers. This was significant for shipping lines wanting to maximise their postal payload and supplement their passenger trade, but especially for aircraft in the early days of aviation. Although it was possible to come down at sea and be rescued, this was not the norm. Ditching a plane in the water was a deadly prospect, even with a parachute.

The design of aircraft in the late twenties and early thirties moved towards refining monoplanes. The earliest aviators had trialed monoplanes but predominantly used biplanes, and even triplanes in order to find sufficient lift to respond to underpowered engines. These were of necessity fragile structures of fabric and wood in order to avoid unnecessary weight. The physics of air flight was largely unknown at the time, though it was recognised that wings needed to be stable in order fly. Previous trails with flapping wings were dismal failures!

European designers and engineers were very keen to develop the initial designs of the type used by the Wright Brothers, who wanted to keep their original design secret. However the basic concepts were becoming more widely known. By 1915, early monoplanes were in production, with the wings being held in position through external wires and braces. The most successfully monoplanes were German designs. In practice, unlike biplanes, they were cumbersome and awkward to manoeuvre, hence not widely used in World War 1.

However, as is often the way, the pressure of war and increased budgets gave a boost to aircraft design. The monoplane became the favoured design, and several versions were developed with different wing positions. By this time the physics of flying were also having an influence. Previously lift had been the primary concern, but increasingly the other factors, downforce, drag, and the impact of winds, were recognised and incorporated into the designs.

One such designer was Edgar Percival. An Australian who had been captivated by flying from his first encounter with a pioneering aviator in 1911, when he was thirteen. He then went on to study aeronautical engineering as it was then.

In 1915, he volunteered in the Australian Imperial Forces and was sent overseas to the war. The next year he was transferred to the Royal Flying Corp, promoted to Captain and was a founding member of the 111 Squadron and elected to the Royal Flying Club in 1919.

After a period back in Australia, Percival continued his interest in flying and aircraft design. He returned to England in 1929 and was appointed as an Air Ministry test pilot. His early aircraft design was unable to find a manufacturer so he set up his own company in Kent.

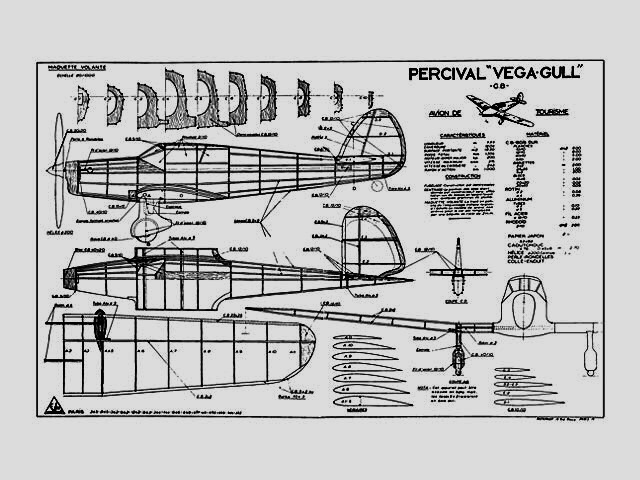

One of his most successful designs was the light aircraft, the Percival Gull. In 1934 he set up his own factory at Gravesend Airport. His planes were flown successfully by other aviators as well as his own race winning efforts and became very popular. They were fast and capable of taking extra fuel tanks.

As a result three women aviators flew the Percival Gull in their record breaking attempts. Amy Johnson set the record for the flight to Cape Town, Jean Batten set the record for flight time between Senegal to Brazil, and Beryl Markham set the record for flying from Europe to North America.

Beryl Markham was born in England and grew up in Kenya, where she learned to fly. To all accounts, her personal life was rich with affairs and several marriages, and she moved in quite privileged circles.

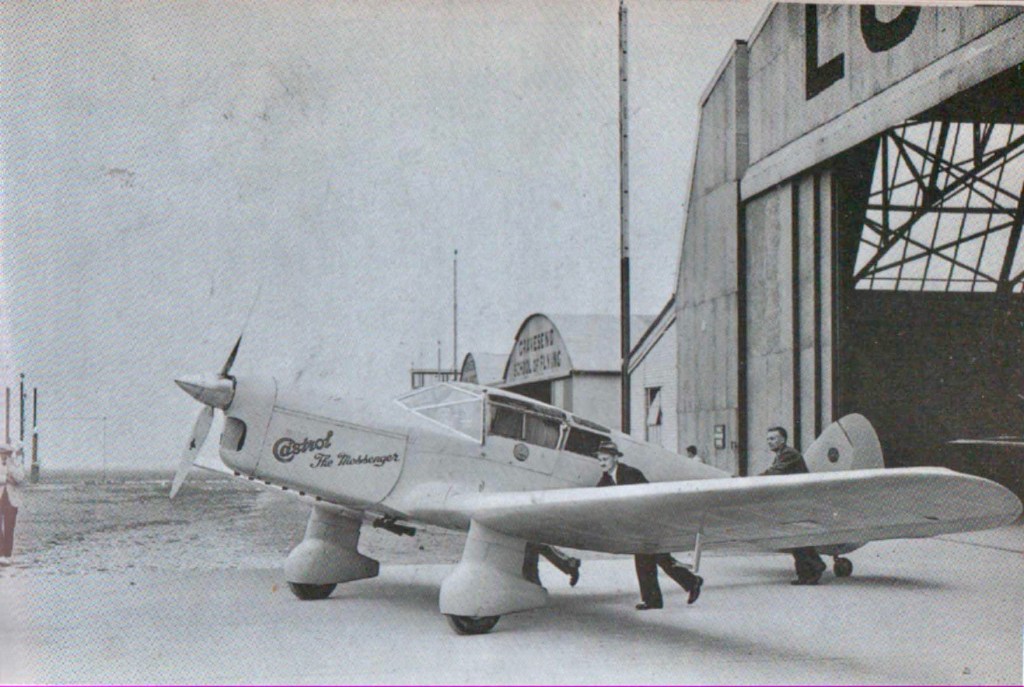

When in England, she was able to negotiate with John Carberry to borrow his freshly delivered Percival Vega Gull, VP-KCC, named The Messenger. He intended to fly it later in the month as part of a race to South Africa, but lent it to Beryl Markham on the understanding she would have it back and airworthy by then.

John Carberry had confidence in lending his plane to Beryl Markham because she was by this time an experienced pilot and mechanic, multiply certified. Edgar Percival was also involved and assisted in the installation and function of the additional fuel tanks needed to make the long journey.

The plane was fitted as standard with four seats, two in the back for passengers. In addition to the extra tanks fitted in the wings and centre section, Percival fitted two auxiliary tanks on the back seats which gave an additional 255 gallons of fuel. This extended the flying range to 3800 miles from 660 nautical miles.

Because of the additional weight, Captain Percival recommended that she flew out of Abingdon Airport which had a runway of a mile. The weather however was very stormy, and the flight was delayed for three days until September 4, 1936. By this time Beryl Markham was impatient with the continuing bad weather and took off in the early evening at around 6pm. The wind was so strong, she was airborne in 600 yards.

Before the journey started, she decided that her priority was warmth, and so she discarded a parachute for additional layers. The engine was air cooled and heating didn’t feature as a high priority in the early planes, There wasn’t a lot of space and she needed to manoeuvre within the cabin to turn on the valves for the extra fuel.

This in itself was difficult because of the lack of fuel gauges in the additional tanks, and the threat of an airlock that would block the flow. The engine was a de Haviland Gypsy, and Percival had suggested for her to let each tank drain, before opening the next. His faith in the engine was such that if it died through fuel starvation, he believed it would automatically restart as they wouldn’t fail.

The weather continued to be so stormy that Beryl Markham had to fly quite a lot lower than she would have usually, at 2000 feet. Any higher and there was the danger of the rain turning to ice, and lower she be blown to into the sea. There was no visible moon, and her carefully prepared chart had flown out of the cockpit window soon after takeoff. She flew completely reliant on her instruments and her maps. There was no radio.

The wind continued against her remorselessly and her speed was averaging at 90mph rather than 150mph cruising speed that the plane was capable of. This impacted on her fuel use as well and it was correspondingly higher than anticipated. She flew through the night, checking her instruments continuously, in the fog and squalling rain, eating the chicken sandwiches, nuts, raisins and dried bananas she had brought with her, with flasks of tea and coffee.

There were moments of peril as the engine cut out, and though restarting as promised, at one point she was stalled within 300 feet above the ocean. Her night was punctuated by flashes of lightning, but on that dark and stormy night Beryl Markham was totally reliant upon her navigational skills.

In the dawns early light, she had glimpses of land ahead, the coast of Newfoundland. From there she was able to calculate a course to Cape Breton in Nova Scotia, four hundred miles away. This is where she planned to refuel. However the ice was sporadically blocking the fuel input. It was resolved briefly if she descended but then reformed as she gained altitude.

With her engine dying she made her way towards the cliffs. The beach was too rocky to land on, so she stuttered her way to an emergency landing just as the engine died. She landed nose down in a peat bog, her head cracking the cockpit glass as she did so. She stumbled from the wreck 21 hours and 15 minutes after leaving Abingdon Airport. Some fishermen came up to her, and she greeted them by saying, “I am Mrs Markham. I have just flown from England.”

Beryl Markham initially considered that she had failed in her quest because she hadn’t reached her original destination, New York. However, she was quickly picked up and lauded for being the first person to fly solo east to west from Europe. It was an extraordinary feat of endurance and skill.

Her return journey back was in the luxury of RMS Queen Mary, accompanied by the slightly battered Messenger. Although not repaired in time for Carberry to take part in his planned race, it was sold on and had several more years of service. Beryl Markham wrote her own account of the journey in the book, West with the Night. Her biography was written much later in her life, Straight on Till Morning, by Mary S Lovell.

Additional references.

https://simpleflying.com/the-evolution-of-the-airplane/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Percival_Gull

Leave a comment